Tell me how to fix it

We all want answers.

It’s the rare human who is willing to sift, sort, and plow through all the possible connections in our biomechanical universe to find them. Most of us like our habits and we settle on “good enough” movement to get through the day.

I just read an article about a historian reading source material to solve a mystery of something that happened 800 years ago. He used AI to look through this material, which was helpful—to a point. The AI program could not make relational connections between the material to reach the answer. It couldn’t “see” how it fit together, even though the data was there.

He comments, “The chatbots failed. Though they were able to parse dense texts for information relevant to the baptistery’s origins, they ultimately couldn’t piece together a wholly new idea. They lacked essential qualities for making discoveries.”

This is the magic of human thinking: We can make relational connections that allow a new perspective, or a new paradigm, or a new idea, to emerge. We make connections for ourselves, through ourselves, and using ourselves.

Thomas Edison, and Moshe Feldenkrais, valued mistakes. Moshe Feldenkrais always said the best learning comes from “mucking about” and “failing well.” Edison said that he doesn’t view mistakes as failures, rather as opportunities to find out what doesn’t work. That’s why we learn movement the way we do: A discovery made on your own terms is worth a million times of being told what to do.

People ask me all the time why the Feldenkrais Method does not simply demonstrate the right way to do things. I’ve just been asked this again, so here is my recent answer:

Imitation is not learning

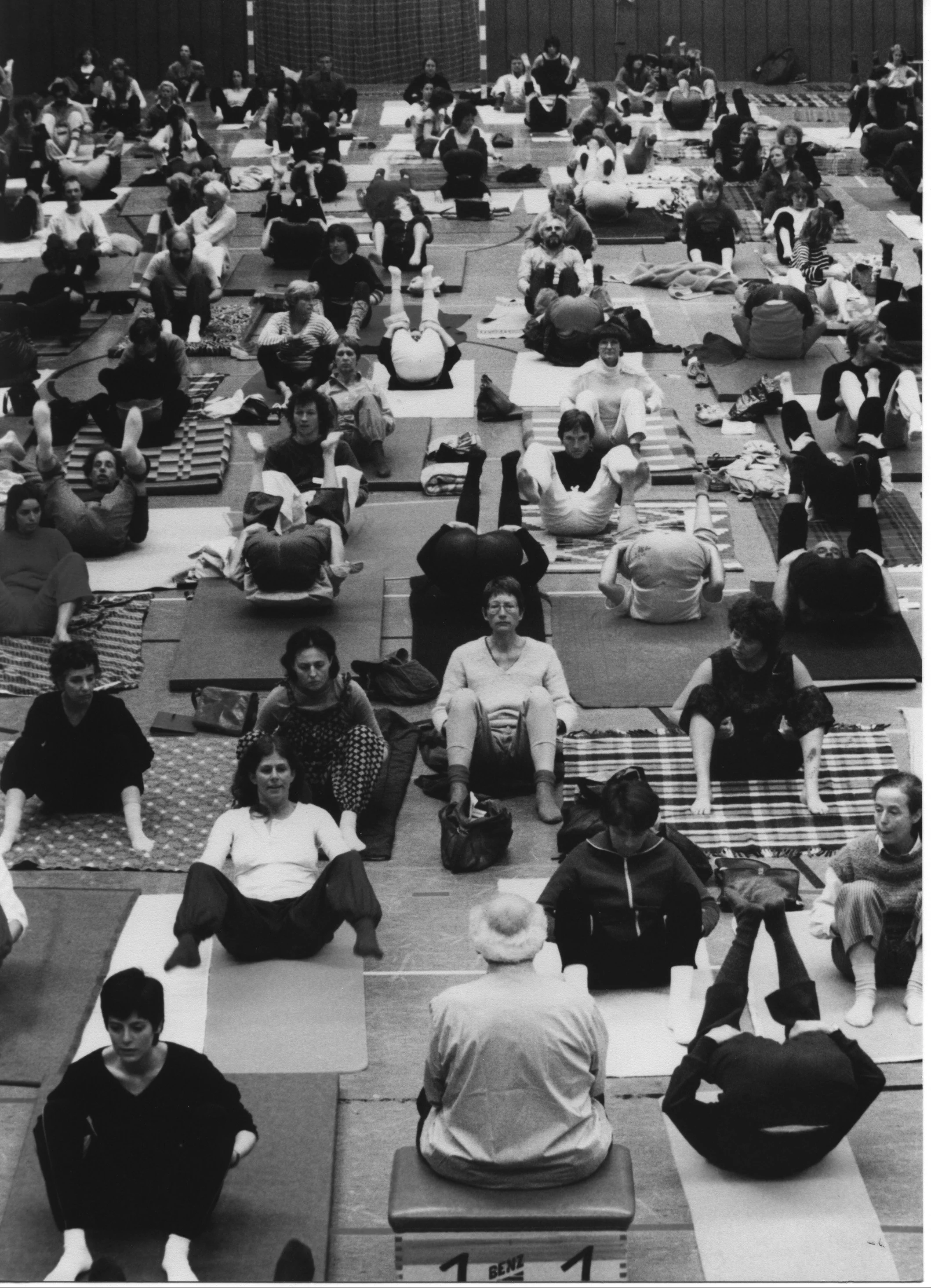

Moshe teaching at Amherst.

Actually, Feldenkrais is not taught via video! Mimicking another person‘s patterns is antithetical to sensing your own nervous system. There is never any demonstration in a class. Visual input will fail you as a learning strategy. Why? Because imitating is not learning.

If you want to be free from compulsion, stop mimicking other people and start sensing how YOU move. The point of a lesson is not to study someone else's strategy, but to discover your own.

In our culture there's a premium on performing rather than exploring, perfecting rather than testing. In Feldenkrais, and any kind of motor-control learning, there is no correcting, fixing, or performing. The point is to discover how you move and where you feel comfort, ease, and connection.

If you copy my way of lifting an arm, it may not be right for you and your personal history of pain, self-use, injury, etc. The variability in human nervous systems is vast, and my injuries have created compensations different from yours.

Just think: Babies do not learn to walk from a power-point presentation. They test, evaluate, and test again. They fall down and get back up. This is called "bottom-up learning" in learning theory, any kind of system processing or ordering of knowledge. In the human system, top-down learning is the executive function of your prefrontal cortex telling yourself off. “Do this, do that, stand up straight!” etc.

In Feldenkrais, we use bottom-up learning, which is about curiosity and experimentation.

Honor your own process

There are no two human nervous systems who will sort through sensory data in the same way. They might land on the same solution, given similar biomechanical constructs, but we all need time to explore and test, even as adults. And, I can guarantee you, no Feldenkrais teacher anywhere in the world will demonstrate what you're "supposed" to do.

There are lots of youtube videos out there, of course. I have some up there as well. That's great, but it does not offer you access to the richness of your nervous system's potential. The practice is called "Awareness Through Movement" after all.

It also does not work to look at a movement on a screen or even at a person, then try to do it, then look, then try, then look, then try. The idea is to go deeper into your own internal sensing. You do this to improve the four aspects of movement:

Timing (when you move)

Orientation (in what direction)

Speed (how fast)

Force (how hard)

Feldenkrais lessons invite you to notice these things in yourself. Motor-control learning, which is what we're doing here, is based on sensory feedback, which, I imagine, is the skill that you are seeking to develop in the service of some goal, like moving better, feeling more balanced, more coordinated, etc.

Here is my note on how to benefit from these lessons. It will help orient you to this type of learning. If this practice does not resonate and you want something with more form and perfection, I get it. This is not that. It's more childlike and curious.

I also have a lot of background articles on how humans learn and how Feldenkrais works if you enjoy a more cognitive approach. I know I always like that aspect of learning and I had to read a ton before I got on board with all this!

More background articles for those curious about the Method:

The Feldenkrais Method and Dynamic Systems, by Mark Reese, PhD: A precise explanation of the technical aspects of the Method.

From Body-oriented Psychotherapies to Feldenkrais, by Yvan Joly, psychotherapist and Feldenkrais trainer®: How Feldenkrais helps us evolve into secure beings and resolve conflict.

Learning How to Learn, by Dennis Leri, Feldenkrais trainer: The best overview of the method’s origins and development.

Why don't you just tell me how to move? If there is a right way to move, why don’t you just say so? It’s so irritating to have to figure it out for myself.

How to Do Feldenkrais: Principles for approaching movement.