Excerpt from Higher Judo: Groundwork

An excerpt from Dr. Feldenkrais's book, Higher Judo: Groundwork

The essential aim of judo is to teach, help, and forward adult maturity, which is an ideal state rarely reached, where a person is capable of dealing with the immediate present task before him without being hindered by earlier formed habits of thought or attitude.

Chapter 1: Judo Practice

To help teach and foster adult independence seems a formidable task and it seems difficult to know how and where to begin. What do we do in judo that is so different from other disciplines?

(There are five factors Dr. Feldenkrais mentions. This elucidates the first three.)

The most striking thing is that judo ignores inheritance as a factor of importance. We do not find that size, weight, strength or form have much connection with what a man can learn to do so long as it is within the limit of his intelligence.

Furthermore, by admitting frankly the physical shortcomings, we are capable of turning to them into advantages in due course! What a man can do now is mostly determined by his personal experience, habits of thought, feeling and action that he has formed.

Usually incapacity to do is produced by fear, imagination, and otherwise distorted appreciation of the outside world. Judo teaches an unemotional, objective activity which has nothing to do with what the person is or feels and we show that the result depends entirely on when, what, and how a thing is done and on nothing else.

The result is that a small, sometimes insignificant physical body of sixty years of age or over can control a powerful youth as if the latter has no will of his own. This is possible only by the impersonal, unemotional and purely mechanistic habits of thought and action inculcated by judo practice. Here is what we do to achieve this.

Factor 1: Bare Feet

First of all, judo is practiced with bare feet. Many people have never made any but the most primitive use of their feet, with the result that the only use and idea associated with them, is that of a plate-like support for the body. This being the only use made of the feet for many years on end, the muscles are most of the time maintained in a fixed state of contraction—precisely the one that makes the feet fit for the service demanded of them.

In extreme cases the exclusion of other patterns is so complete, that the feet become frozen in the flat, plate-like position and are almost useless for any other purpose than motionless standing.

When required to change shape, that is, to alter the pattern of contraction of the different muscles and consequently the relative configuration of the numerous bones of the feet, some muscles are too weak and do not contract powerfully enough, other muscles and ligaments are too short and their stretching to the unaccustomed length is painful.

Such persons are forced to assume queer positions of the legs, pelvis and the rest of the body to make movement possible while maintaining the feet in the accustomed way. They tire more quickly than other people, become irritable, their movements lack swing and ease and they are peculiar in many other ways.

The number of people with very little or no control of their toes and whose gait and general body carriage is affected by it is considerable. The important thing is, of course, not this quite minor infirmity, but the fact that the central control has some part of it excluded from functioning and that such people are capable of only pre-selected acts.

When this happens in the optical centres, or any other of the centres on which our mobility depends more directly, the results are obvious and each case has even got a special word for describing that infirmity.

To some extent, more or less total withdrawal from use of any of the acts of which we are capable, is an infirmity and has a profound effect on our behavior. We shall deal with this more fully later on.

In the light of what has been said about adult independence, persons only capable of a very restricted use of their feet may be considered as only having achieved a childish degree of independence of their feet, as they can make of them solely the primitive use of standing, proper to a child of a certain age.

The understanding Judo teacher does his best to further the maturing process of his pupils in this respect, showing them that it is essentially a question of learning and not of infirmity.

Often quite apart from the local improvement, a remarkable increase in general vitality can be observed in the pupil who has learned a more differentiated and varied use of his feet.

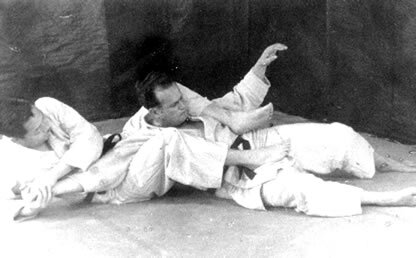

Factor 2: Falling

The second most striking feature of Judo practice is the art of falling. Mots people learn to maintain upright carriage for considerable periods and never further their adjustment to gravitation beyond this infantile state. Our parents themselves being clumsy and incapable of falling without more or less inconvenience or injury, cannot help themselves but pester Johnny with “be careful, darling,” every time Johnny attempts to learn for himself how to control his body in trying situations. Johnny then grows like his parents—unable to fall without hurt and afraid of any sudden change of position.

The fear of falling, or more correctly, the reaction to falling, can be observed immediately after birth. Again, therefore, by teaching the art of falling properly, we further the person's maturity towards a more adult independence of the gravitational force.

In some people we observe a fear of falling so great that we must take special precautions and care in teaching them to fall. They stiffen themselves so strongly even if their balance is ever so slightly compromised, that the body presents numerous angles which make contact with the ground very harsh and uncomfortable.

In general, we find such persons also presenting marked inability to use their feet. This is not at all surprising. For the control remaining in an infantile state, their experiences is that any forced change of position, when unexpected, means hurt.

Most people are rarely aware of the deeper motivation behind their general disposition, likes, and dislikes. The above formulation of the childish state of independence from gravitation may seem trifling to the layman as well as to the person himself.

It is worth pondering over the fact that through with great perseverance it is possible to achieve a certain degree of professional efficiency in dancing, football, skating or the like, occupations in which mobility must be of a high degree of perfection, the state where one works not only from necessity but enjoys the pleasure of creative work, is never achieved before adult independence from gravitation.

It is important for the Judo teacher to be clear in his mind on this point so that he does not present his pupil with too stringent a tasks but gives generous and patient assistance. His reward will be the growth of the expanding personality of his pupil, to whom he restitutes what general ignorance has robbed from him—the means of developing a mature and harmonious personality.

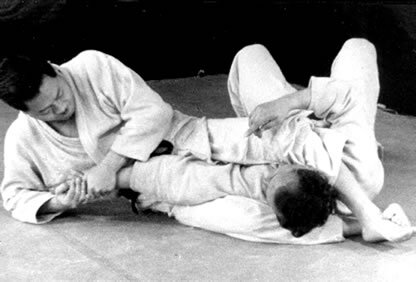

Factor 3: Novel Use of Self

The third point in which judo differs from most disciplines is that from the first lesson the pupil is taught to use his body in a way fundamentally different from his own. It may beg the question whether a fundamentally different mode of action from the one we are using could be a better one. Our way of action is formed in a society where organized security and the belief that inherited personal qualities are things to be proud of and defects to be ashamed of and hidden.

Habits of thought and action formed in this way are of little avail when we are confronted with tasks in which our social standing cannot influence the outcome of the act. The proper activity is such that the aim set to ourselves can be achieved in most circumstances. This demands flexibility of attitude of mind and body quite beyond that which we form in the present social environment.

Normally we learn to anchor our bodies in a statically secure stability with the object of defending our “honor,” or “standing,” by the exercise of greater force. In Judo we teach a functional stability, precarious for any other purpose for any length of time, but solving the immediate problem in front of us or the act to be performed. We seek to mobilize on the present situation all we have, throwing away all that is useless for the immediate purpose.

The experienced Judo practitioner, like the scientist, has learned to test ideas by their experimental value. The word dynamic, when used in connection with human action, generally conveys the idea of something better than static. In mechanics there can be no such emotional favoritism—both static and dynamic stability have their place in the general order of things.

In the same way there is no reason why, because we teach a “different” or “new” way of using one's body, that it should be any better than the old one, or that it should be any good at all.

The justification is, that this “new” way and the dynamic stability are found in all those who have had a favorable history of growth and have succeeded in reaching adult maturity in most of their power.

The Judo way is new only to people for whom the road to correct development is barred; their personal experience has led to inharmonious development, instead of a broad and even exercise of all their powers. Some parts of their personality are over-active and others totally or almost completely excluded from use.

Dynamic stability is as proper to the human frame as speech; both grow through primitive and rudimentary stages to adult maturity. The majority of people leave off the maturing process before it reaches its ultimate level. Let us see the reasons why dynamic stability is so important to man.

Dynamic Stability

The human method of erect carriage is considerably different from the bipedal posture that animals may assume for shorter or longer periods. When erect posture is held properly, rotation of the body around the vertical axis needs very little energy. The pirouettes of the dancer or skater are repeated a considerable number of times, thanks to the initial impulse only, and with minute additional effort.

In any other position, say, just spreading the arms and legs, even a considerably greater initial effort does not allow the performance of much more than one complete turn or so. In mechanics, we say that the moment of inertia of the body is greater when there is mass farther away from the axis of rotation.

The moment of inertia increases very rapidly as the distance of the mass from the axis of rotation grows. It increases with the square of the distance, that is, when the distance is doubled, the energy involved is fourfold. Thus people holding themselves strictly upright have greater facility for rotation.

The perfect bullfighter, at the moment of the kill, shows this to the utmost. He raises himself on to his tiptoes, stands as narrowly as he can, keeps his elbows close to his body and his head upright until the last instant. This attitude enables him to turn out of the way of the dashing bull in the nick of time.

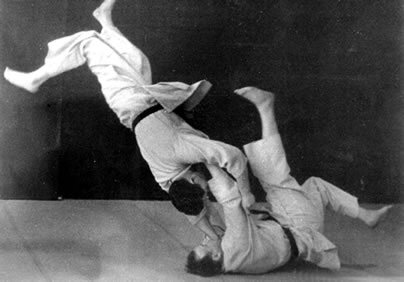

The observant judo student has certainly noticed that hip and shoulder throws, in fact, all throws that involve rotation of the body about half a turn around itself, take a much longer time to learn. Some people, partly because the teacher himself is not very clear in his mind about the principle involved, have never won a contest by one of these finest throws of the judo repertoire.

Spectators are generally very appreciative of such throws; they probably imagine themselves performing such movements and realize how perfect the independence of gravitation must be to do so. It is unlikely that they give themselves a rational account of their feelings in terms we have used. The expert is recognized by his ability to bring off such throws successfully at will.

Dynamic stability is acquired through movement, such as the stability of a top or that of a bicycle.

A top of a bicycle may be so shaped that it is impossible to make them stand still unsupported, but once set moving, there is little difficulty in maintaining their centre of gravity above their point of contact with the ground. Before a movement is completely arrested, there is obviously an instant where the stability passes from dynamic to static stability. (A Judo practitioner perched on one toe in mid-throw can only remain so for a transitory instant.)

The performance of any act while we are in motion is exhilarating. The uncivilized man, the ape, the cat and other animals depending mostly on their body skill for their maintenance, develop their independence from gravitation to the limit of their nervous system.

The civilized man stops developing directly he acquires a control barely sufficient to get on with in his organized and well-selected environment. Often, therefore, individuals have a very rudimentary independence from gravitation and when they happen to perform a movement with greater perfection than usual the are thrilled by the feeling.

The thrilling feeling is quite common in most methods imparting body skill and becomes frequent with the better exponents. In judo it is the essence of the training; training is not complete until the pupils can produce these states at will and in spite of the opponent's resistance.

All the finer throws and most of the others are performed while the body is rotating and only on one foot at that. The degree of independence from gravitation needed for that is far above the usual level in our daily lives, and higher than that of most other methods.

The importance of this becomes quite clear when we examine the essential difference between human erect carriage and that of any other animal. The human body is best fitted for rotation around its vertical axis, and when this is performed on one toe, with all the members held near the body, it is swift and practically effortless.

“In short, judo furthers the gravitation independence to such a degree that, compared with the average man, the judo practitioner is free to attend to the act he is performing, while the untrained man has to keep his attention burdened with the business of keeping balance on two feet—a laborious and slow task.”

The untrained man finds only part of his attention free to deal with the opponent's action and is so engaged in preserving balance in the most primitive standing position, on two feet, that the only reaction he is capable of is the general contraction of his muscles initiated by his fear of falling.

The slower and the more primitive the mobility of an animal is, the more is its reaction to forced change of position similar to that of the untrained man. Thus, the cat never resists, that is, never stiffens itself when pushed; it finds a new standing configuration so easily that abandoning the old one is no threat to it.

The slower and older an animal, the more reluctant it is to move, and is therefore inclined to stiffen itself and resist displacement. In man the reasons for resistance are more complex, because of the social significance of being pushed.

Static Stability

The static stability of the human body is very precarious. The heaviest parts are in fact placed very high above a relatively small base. The height of the centre of gravity divided by the standing surface, or more precisely, by the area of sustentation, gives a ration which is larger for man than that of other mammals.

Thus, even a rough estimate shows how different and precarious human standing is, from the point of view of static stability. The horse, for instance, has the centre of gravity about six feet off the ground and stands on something like twelve square feet. The ratio which is roughly an index of stability is half. In man, the ratio is three feet over one square foot, i.e., about three on the average, or in other words, six times worse than that of the horse. The same result is roughly maintained in all comparisons with most of the animals walking on land; their stability index is most of the time even better than that of the horse.

While the nervous system is not fully developed, the child has very little freedom for rapid adjustment and the toddler stands with his feet very wide apart. He increases his base as much as he can and falls when this is not sufficient to preserve balance. The ultimate stability of the adult body is secured by the facility of adjustment to the vertical and not by increasing the base or lowering the centre of gravity.

Adult erect standing is therefore not derived from static principles. It is essentially a continuous regaining of unstable equilibrium from which the centre of gravity is constantly drifting away, even while standing still. The momentum of the circulating blood, breathing and other motions in the body, as well as minor stimulations of the muscles, especially those of the head, are reasons why static stability of the body is rarely achieved.

We may say, therefore, that the adult body stability is dynamic and that relying exclusively on the size of the standing base and lowering the centre of gravity, is truly an infantile feature. In decrepit old age, we again revert to the infantile mode, as we do in most other things.

In furthering adult individual independence from gravitation Judo stands so far above any other method that it is little exaggeration to say that it stands alone. Though certain skills such as jumping, for instance, may further this development even beyond the Judo level, Judo cultivates adult independence in the entire solid angle.

From the foreword by Dennis Leri, Feldenkrais trainer:

The joy of learning, practicing, and accomplishing is all the more valuable because it is a feeling one cannot buy. It can only be achieved through one's own labors, through a complete reeducation of one's thinking, sensing, feeling, and acting. It comes through utilizing the art of self-defense as a means to a realization of one's true nature harmonized with Nature or the cosmos itself...The practitioner blends their practice with their true nature to make new modes of action second nature.

The Greeks called this process phusiopoiesis: making one's nature a seconding of the unceasing movement, ordering, and presencing of nature. In fact, it was a central concept along with kairos (timing) in ancient Greek martial arts training. Kairos had an ethical, aesthetic, and pragmatic meaning, referring to the impact of the right technique applied at the right time and for the right reason. Phusis and kairos were related, not as matter and time are in modern physics, but related to a kind of knowing that one could achieve through training.

Knowing in this sense indicates a kind of physicality and awareness, which, when present together, show us life itself—making us yearn to train more, to be able to enact our knowledge not only now and then but for as long as we live.